Meet the Wounded Warriors Who Will Join Us on High Seas Rally 2024

February 6, 2024

In addition to the High Seas Rally Dialysis Fund, in 2022 we expanded our mission to support Veterans and Service members with our partnership with Wounded Warrior Project.

Since 2003, Wounded Warrior Project has been meeting the growing needs of warriors, their families, and caregivers — helping them achieve their highest ambition. High Seas Rally is proud to announce that we will fund six all-expense paid trips this year for Wounded Warriors and a companion. This year we are excited to announce six Wounded Warriors, three of which sailed with us in 2022, and three Wounded Warriors who will be joining us for the first time. Each Warrior and their companion will receive round trip transportation to the cruise, a cabin on the ship and $500 in onboard credit to help these deserving recipients enjoy the World’s Only Motorcycle Rally on a Cruise Ship™.

In addition, all fundraising efforts on Salute to Service Day on the 2024 cruise will go directly to the Wounded Warrior Project.

Read the inspirational stories from the six Wounded Warriors who will be joining us on High Seas Rally 2024.

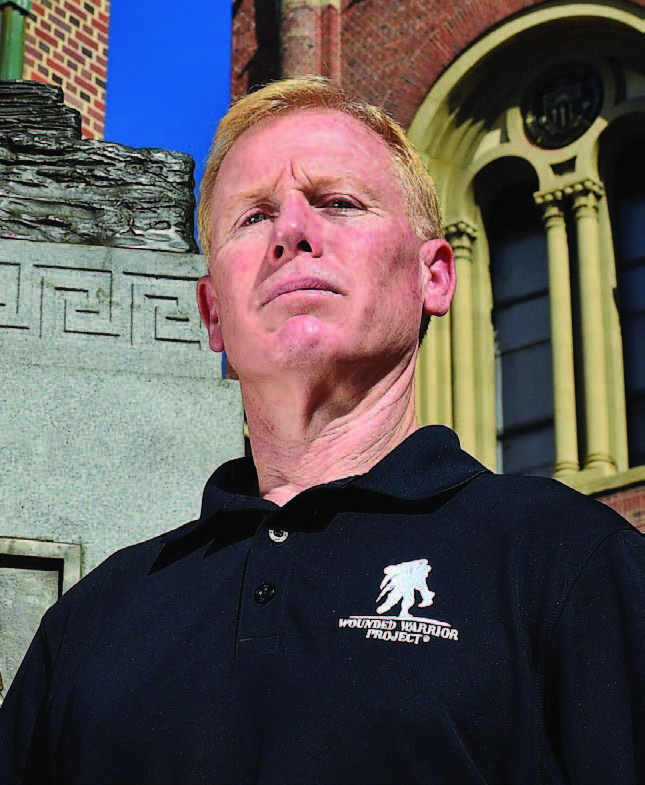

Ray Andalio

Ray Andalio was born in the Philippines and immigrated to the United States when he was 14 years old because of a revolution in his homeland. He loved and respected the country that sheltered his family and helped them find freedom, and in 1992 he decided to give back by joining the U.S. Navy. He served six years on active duty before transferring to the reserves.

In 2003, Ray was sent to Iraq to serve as a corpsman for a unit of Marines, and his training was put to the ultimate test. “My whole battalion was getting blasted left and right,” says Ray. “Everybody in my unit has something wrong. If they say there’s nothing wrong with them, they’re in denial.”

Ray was injured in April 2004, when the shock waves from multiple explosions caused a traumatic brain injury (TBI) that – to this day – requires him to wear dark glasses to prevent severe headaches. He also lives with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of his experiences. As a corpsman, you’re there to save lives – but the reality of war is that you can’t save everyone. When Ray came home, he struggled more with his survivor’s guilt and PTSD than the physical injury to his brain.

Claude Boushey

Claude Boushey grew up surfing in the waters around Barbers Point Naval Air Station in Hawaii, watching military aircraft take off and land – and dreaming that someday, maybe he’d be a pilot himself. In 1983, he joined the U.S. Army as an avionic mechanic and started to work his way up the ranks. Ten years later, he went to flight school and became a helicopter pilot.

His unit deployed to Iraq in 2004. One day, Claude and his copilot Dwight were on the way to assist at the site of an explosion and ambush when their helicopter crashed into a swamp. The impact shattered and compressed Claude’s vertebrae and compromised 80 percent of his spinal canal.

“Usually, if your spine is compromised more than 40 percent, you’re paralyzed,” says Claude. “But after four surgeries and eight months of grueling rehab, I proved doctors wrong and started walking again.”

Bill Geiger

When Bill Geiger returned to civilian life after two deployments with the United States Army, he was a changed man. His service with the military police in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and Camp Bucca, Iraq, guarding high-value detainees and being exposed to mortar attacks and riots, deteriorated the formerly vibrant man his wife, Sara, once knew.

“I knew something was wrong the first time I hugged him after coming back from Cuba,” says Sara. “His joy for life was gone, replaced by a depressed, anxious, short-tempered recluse.”

Meanwhile, the children walked on eggshells around their father. ‘‘How do you describe a man who yells at you because you dropped a bread crumb on the floor?” Bill asks of himself.

Then one day, Bill saw an email Sara had left open on their family’s computer. It was to their pastor and said, in part: “If I had known Bill was going to be like this, I never would have married him.”

Philip Krabbe

Philip Krabbe’s happiest memories came from the time he spent in the U.S. Marine Corps. “I loved the Marines,” Philip says. “The best part was the camaraderie and the love we had for one another.”

But that brotherhood made the reality of war even more devastating. On May 23, 2006, Philip lost two of his Marines and an interpreter to a roadside bomb. Not only were they his friends, but as their platoon sergeant, Philip felt responsible. He compartmentalized his feelings and carried on with the mission, but it wasn’t long before he needed prescription drugs to get to sleep at night.

When Philip returned home, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and survivor’s guilt led him to continue self-medicating with drugs and alcohol. “I was an alcoholic,” admits Philip. “I was a drug addict, too. I tried to cope the only way I knew how, just to be able to function during the day.”

Angie Peacock

Angie Peacock joined the U.S. Army in 1998 because she wanted a job with meaning that empowered her to help others. When she deployed to Iraq in 2003, just after the initial invasion of Baghdad, her role was to set up and maintain the communication lines for her unit.

“There was danger constantly,” says Angie. “I didn’t know day-to-day if I was going to make it back.”

While in Iraq, she came down with a mysterious illness that caused her to lose 40 pounds and eventually be medevac’d out of the country. But the day after she got to the hospital in Germany, her platoon’s convoy was hit by an improvised explosive device.

“I felt guilty that I wasn’t there,” says Angie. “And I felt shame because I didn’t get wounded like that. I felt like I wasn’t a real soldier because I didn’t get medevac’d out for a real reason.” Angie sought help from the psychiatry team at the hospital, but the help they provided was in the form of prescription drugs. By 2006, she was on 16 medications to combat her post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). That year, she attempted suicide more times than she can remember.

Dan Smee

Dan Smee joined the U.S. Army as a medic in 1983, served his four years, and then went back to living a normal civilian life. But after 9/11, he felt he had to do something to help — so in 2002, he joined the National Guard. They put him in the same job he’d had 14 years earlier, but this time, his combat medic training would truly be put to the test.

On November 10, 2004, Dan was among the first on the scene when an improvised explosive device detonated under the lead vehicle of his convoy. His platoon sergeant, Mike Ottolini, made the ultimate sacrifice for his country that day. Knowing there was nothing he could do for Mike, Dan went to treat Sergeant Nevins, who had also been badly wounded. But after he came home, Dan couldn’t get the memories of that incident out of his mind.

“For years, I carried the images of Sgt. Nevins in my head, half in and half out of his vehicle,” admits Dan. “It was eating me up, and I always wondered if he blamed me for not being able to save his leg.”

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) took over, and Dan felt empty for years. He tried drinking away his problems, but at the bottom of a bottle he only found more problems. Then he found Wounded Warrior Project® (WWP). One of the first WWP events Dan attended was the 2010 Courage Awards — where Sgt. Nevins was one of the featured speakers.